Zanzibar Access Control

Introduction

Zanzibar is an authorization service introduced by Google to manage access control across its services. Its primary function is to evaluate access requests by answering:

Can user U perform operation O on object A?

This article explores Zanzibar's access control model, how it handles access requests, and a conceptual framework for understanding it.

Relation Based Access Control Model

Access control determines who or what can operate on a given resource within a system. Zanzibar implements a model closely aligned with Relation-Based Access Control (RelBAC). RelBAC defines permissions based on relationships between entities. Similar to relational databases and object-oriented modeling, it establishes access rules using entity relationships.

E.g. A book is written by an author. The book and author are connected by the authored relation. This relation implies permissions—an author should have read and edit access to their book.

Such relationships exist across various domains, often represented using specialized languages like description logic. RelBAC leverages these relationships to determine permissions dynamically.

Zanzibar's RelBAC

A key concept in Zanzibar is the Relation Tuple, which represents relationships between system objects.

Relation Tuple

tuple := (object, relation, user)

object := namespace:id

user := object | (object, relation)

relation := string

namespace := string

id := string

A Relation Tuple is a 3-tuple containing:

- Object – The entity being referenced.

- Relation – A named association between entities.

- User – The entity granted access, which can be:

- A direct reference to an object.

- A userset (an indirect group reference).

E.g. The tuple (article:zanzibar, publisher, corporation:google) defines a relationship where Google (corporation:google) is the publisher of the Zanzibar article (article:zanzibar).

Usersets

A userset is a special form of user defined as (object, relation), grouping users who share the same relation to an object.

Example

Consider the userset (group:engineering, member) and the tuples:

(group:engineering, member, user:bob)(group:engineering, member, user:alice).

The userset (group:engineering, member) expands to include Bob and Alice as members.

Recursive Definitions

Usersets introduce a layer of indirection in Relation Tuples, allowing tuples to reference other usersets. This enables recursive definitions, where a tuple can specify a userset that, in turn, references another userset, supporting complex access hierarchies.

The Relation Graph

A key insight into Zanzibar is recognizing that a set of Tuples forms a Relation Graph.

Structure of the Relation Graph

A Relation Tuple can be rewritten as a pair of pairs:

- ((object, relation), (object, relation))

These object-relation pairs are called Relation Nodes. The first pair represents the Tuple’s Object and Relation, while the second represents a userset. If relations are allowed to be empty, this structure accommodates all cases from the original definition.

Each Relation Tuple defines an Edge in the Relation Graph, and each Node corresponds to an object-relation pair.

Example

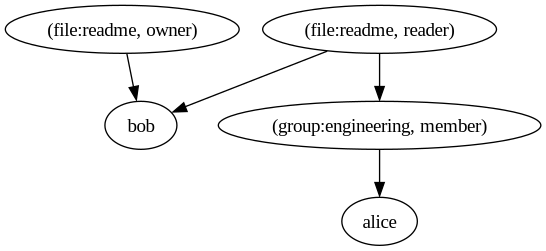

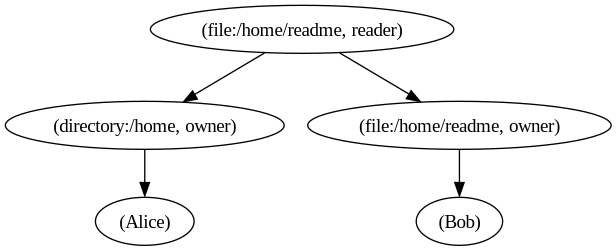

Given the following tuples:

- ("file:readme", "owner", "bob")

- ("file:readme", "reader", "group:engineering", "member")

- ("group:engineering", "member", "alice")

The corresponding Relation Graph looks like this:

Using the Relation Graph

The Relation Graph provides a system-wide view of all objects and their relationships. It enables answering questions such as:

Does user U have relation R with object O?

This question is resolved by starting at node (O, R), traversing the graph, and checking for user U.

If R represents a permission (e.g., "read", "write", "delete"), the Relation Graph serves as a structured way to enforce and evaluate access control.

Userset Rewrite Rules

Relation Tuples provide a generic and powerful model for representing relations and permissions in a system. However, they are minimalistic, often leading to redundant tuples.

Historically, grouping relations and grouping objects have been crucial in access control. Theoretically, these features are essential for Zanzibar to qualify as a Relation-Based Access Control (RelBAC) implementation.

To address this, Zanzibar introduces Userset Rewrite Rules.

Overview of Userset Rewrite Rules

Userset Rewrite Rules are not immediately intuitive.

A rule functions as a transformation on a Relation Node (object, relation), returning a set of descendant Relation Nodes.

Example

Let A be a Relation Node and R be a Rewrite Rule. Then:

R(A) → {B, C, D}

This means that applying R to A produces a set of descendant Relation Nodes {B, C, D}.

Rules are associated with specific relations and execute at runtime, dynamically resolving permissions as Zanzibar traverses the Relation Graph.

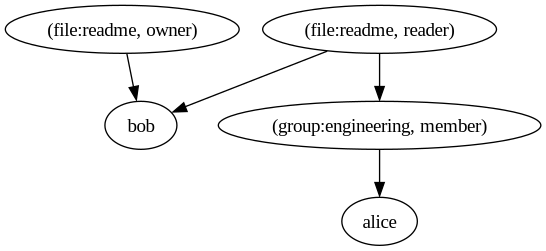

Permissions hierarchy and computed usersets

A permission hierarchy simplifies access control by linking stronger and weaker permissions. If a user has permission to perform a higher-level action, they automatically gain permission for related lower-level actions. For example, the ability to write typically includes the ability to read. This hierarchy reduces administrative effort and simplifies rule management in an Access Control System.

Refer to the following Relation Graph for a visual representation.

In our system, Bob is both a reader and an owner. If ownership always implies read access, maintaining redundant permission tuples adds unnecessary overhead. Zanzibar addresses this with the Computed Userset rule, which dynamically links relations in the permission hierarchy. To enforce that owner always implies reader, we define a Computed Userset("owner") rule for the reader relation. This rule automatically extends permissions without requiring additional tuples.

When checking if Bob has reader access to file:readme, Zanzibar follows these steps:

- Start at the node

("file:readme", "reader")and check for associated rules. - Detect the Computed Userset("owner") rule, which creates a new relation node

("file:readme", "owner")as a successor of("file:readme", "reader"). - Continue searching through

("file:readme", "owner").

This approach ensures efficient permission management by dynamically resolving inherited access rights.

Using a Computed Userset we successfully added a rule to Zanzibar which automatically derives one relation from another. This enable users to define a set of global rules for a relation as opposed to adding additional Relation Tuples for each object in the system. This powerful mechanism greatly decreases the maintainability cost associated to Relation Tuples.

Object Hierarchy and Tuple to Userset

Before exploring the Tuple to Userset rule, let's revisit the core idea of RelBAC: relationships between system objects define permissions and determine access control. We have already seen how Relation Tuples link objects to users and how Usersets establish hierarchies and group users. However, we have yet to define how Zanzibar can create relationships between objects and group them accordingly. This is where the Tuple to Userset rule comes into play.

To illustrate this concept, let's consider a familiar filesystem permission model.

A filesystem consists of:

- Directories, files, and users

- Users who own files and directories

- Directories that contain files

In this example, having read permission on a directory should automatically grant read permission for all files within that directory. The Tuple to Userset rule enables this by defining relationships between objects dynamically.

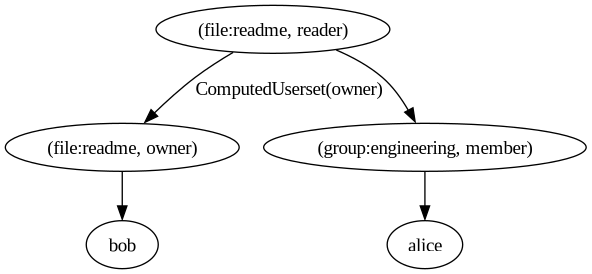

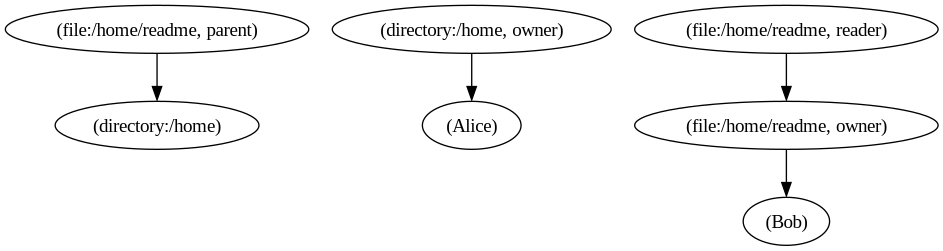

The following Relation Graph illustrates the existing Tuples in the system:

We need to express two key relationships:

- Bob’s

readmefile is inside Alice’s/homedirectory. - Since the file is in her directory, Alice should have read access to it.

One way to grant Alice read access is to create a Relation Tuple that links the file to the directory’s owners.

The tuple (file:/home/readme, reader, (directory:/home, owner)) ensures that directory owners automatically become file readers.

The updated Relation Graph now looks like this:

While this grants the correct permissions, it does not establish an explicit relationship between the file and the directory itself. The Relation Tuple only states that directory owners are also file readers, but it does not indicate that file:/home/readme is actually contained within directory:/home.

To fully represent the structure of the filesystem, we need a way to explicitly define object relationships. This is where the Tuple to Userset rule becomes essential.

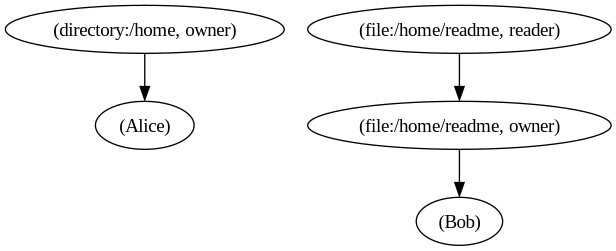

What we truly need is a way to declare a relationship between a file and a directory and, from that relationship, derive the set of directory owners. The following image illustrates this concept:

From this representation, we see that the file is linked to its directory through the parent relation. This explicitly defines the structural relationship between objects in the system. However, to complete the access control logic, we need a way to trace a path from the ("/home/readme", "reader") node to the ("/home", "owner") node.

One possible approach would be to use:

- A Computed Userset rule, linking

readertoparent - An additional Relation Tuple between

/homeand/home, owner

However, this method mixes object relationships with access control rules, making it difficult to separate concerns. This is exactly the problem that the Tuple to Userset rule solves.

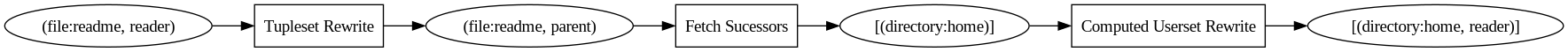

The Tuple to Userset rule is essentially a Tuple query combined with a Computed Userset rule. It takes two arguments:

- Tupleset Filter – Specifies the relation between objects

- Computed Userset Relation – Defines how permissions should propagate

- The rule first rewrites the current Relation Node using the Tupleset Filter.

- Using this new node, it fetches all successor nodes.

- The successor set is then processed through a Computed Userset Rewrite, applying the supplied Computed Userset Relation.

The Tuple to Userset rule is powerful because it allows an application to declare relationships between objects without embedding access control logic in the application itself. This enables object hierarchies to be seamlessly translated into access control rules.

The key benefit of Tuple to Userset is that applications only need to create Tuples expressing object relationships—without extra tuples just for permission derivation.

This has profound implications:

- Applications no longer need to explicitly track access control logic.

- The rules of access control remain entirely within Zanzibar.

- The application layer is unaware of access rules, focusing solely on object relationships.

By enabling complex object hierarchies to be natively converted into access control rules, the Tuple to Userset rule fundamentally decouples permission management from application logic.

Finally, let's see the TupleToUserset rule in action.

Let the rule TupleToUserset(tupleset_filter: "parent", computed_userset: "reader") be associated with the "reader" relation, and assume the same Relation Tuples as shown earlier.

Evaluating the TupleToUserset rule follows these steps:

- Start at the Relation Node

(file:/home/readme, reader). - Evaluate the rule

TupleToUserset(tupleset_filter: "parent", computed_userset: "reader"). - Build a filter using

"tupleset_filter"->(file:/home/readme, parent). - Fetch all successors of the filter from step 3 ->

[(directory:/home)]. - Apply a Computed Userset rewrite rule using the

"computed_userset"relation for each fetched Relation Node ->[(directory:/home, reader)].

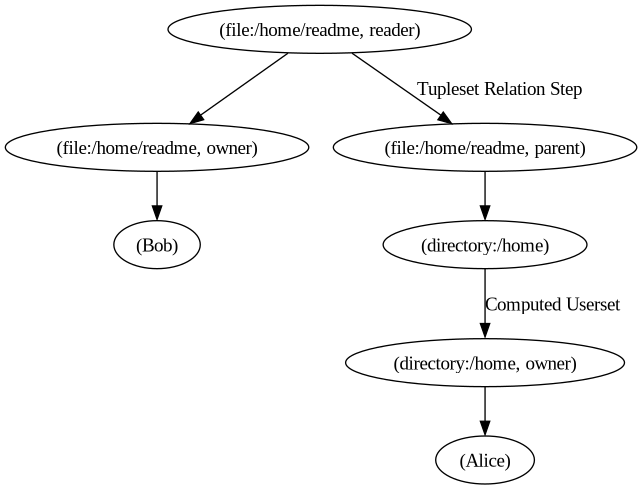

This process ensures that the "reader" permission propagates correctly through the object hierarchy. The following image further illustrates the concept:

Effectively, the Tuple to Userset added a path from the /home/readme, reader node to the /home, owner nodes.

The following image shows the edges the rule added:

Rewrite Rule Expression

In Zanzibar, a relation can have multiple rewrite rules. These rules are combined to form Rewrite Rule expressions. Each rewrite rule returns a set of Relation Nodes (or usersets), which are then combined using set operations defined in the Rewrite Rule Expression. The available set operations are union, difference, and intersection. When evaluating each Rewrite Rule, the resulting sets of Nodes are processed through these set operations. The final evaluated set of Nodes represents all the successors of a parent Relation Node.

Conclusion

The Relation Tuples define a graph of object relationships, which is used to resolve Access Requests. Usersets enable grouping users and applying relations to an entire set of users. The Userset Rewrite Rules allow the creation of Relation Hierarchies and support Object Hierarchies. These features are critical for keeping Access Control Logic within Zanzibar. While the Relation Graph was useful for illustration, in practice, Zanzibar dynamically constructs the graph from Relation Tuples and evaluates the Rewrite Rules. This synergy between Relation Tuples and Rewrite Rules powers Zanzibar’s Access Control Model. From this perspective, Zanzibar’s API operates on the dynamic Relation Graph. The Check API call corresponds to a graph reachability problem. The Expand API serves as a debugging tool, exposing the Goal Tree used during the recursive expansion of Rewrite Rules and successor retrieval.